Cornell University College of Architecture Art and Planning Majors

Office Hours: Paul Ramírez Jonas: Cornell Academy College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP)

1. Why did y'all decide to go into pedagogy?

In 1994, Jack Risley asked me to teach a class at NYU, and I found out, much to my own surprise, that I dearest teaching. I have grown a tremendous amount as an artist and a person through teaching. It has kept me in constant dialogue with others too as provided me with a mirror for self-awareness. The classroom is a context where I can gain altitude from my own work. Teaching allows me to empathize, accept, and understand work that is radically different than mine. This change in perspective offers the perfect antidote to the state of mind I bring to the studio—a mindset that is by necessity much more focused and narrow.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

Since that first didactics job, I have non stopped teaching. I have taught a lilliputian bit of everything including graduate critiques, courses on the performative object, beginning drawing, advanced sketching, and unlike levels of sculpture. I developed a robotics class, studio and seminars on public art, and more recently, courses on publishing and the public sphere. I take also taught at a variety of schools and accept observed what makes some schools piece of work meliorate than others. I have stayed circumspect to the curricula, asking: What types of foundation courses seem to work all-time? Every bit art practices go along to expand, what baseline of techniques should we provide undergraduates? And every bit a plurality of ideas and ideologies refuses to settle, what minimum and best theoretical base should we teach graduates? However, the question that still inspires me the about is how visual arts might fit inside education at large (and across academia, in club at large). During my own undergraduate years, I took courses in comparative literature, linguistics, mathematics, intellectual history, and non necessarily because I wanted to be a writer, linguist, or mathematician, etc. Most importantly, these classes had something to offer those outside the field while maintaining the rigor expected of those majoring in those subjects. Likewise, I strive to make my classes simultaneously enriching for future artists as well equally the curious visitor from another field. This is particularly meaningful when one considers how few people who study art actually become artists. Ideally then, an art pedagogy should exist useful for those who choose to follow unlike paths. Art education can teach students a useful approach to life, one where there is a relationship between significant and form; 1 where they empathize their chapters to shape that relationship.

I was drawn to Cornell considering it is a inquiry university where every department is dedicated to education, research, and creating new noesis in their field. In general, this is the perfect environment for what I described above. Specifically, the Department of Art sits within the College of Compages, Art, and Planning (AAP), and in researching the position I read their mission statement: "At the Higher of Architecture, Art, and Planning, we prepare our students to accost the greatest challenges of the 21st century through applied research, creative practice, and community-engaged planning. We encourage imagination, technical creativity, critical thinking, and embrace transdisciplinary approaches to building a more beautiful, sustainable, and equitable world." This sense of ethical purpose drew me to the schoolhouse.

3. What theory and art history practise you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do y'all refer to most ofttimes?

We live in a time when the visual arts are pivoting from being defined past exclusion to becoming more inclusive of diverse cultures, histories, techniques, traditions, forms, contents, and methods of apportionment and distribution. From a pedagogic perspective, I have felt the insecurity of wanting essentials. Duchamp said, "Art is a game between all people of all periods," and I agree! I want to be brave and say there are no essentials. I am still trying to be that dauntless.

Paul Ramírez Jonas, Culling Facts, 2017. Spare change supplied past the public, notary public seal and postage, signature, ledger, leather desk pad, gold electroplating kit, scale, pyrite, paper, a golden melting and casting kit, paper, and a folding tabular array. Photo: Scott Rudd.

four. How do you lot navigate generational or cultural differences between you and your students?

The just way I tin can do this is to embrace Paulo Freire as tightly as I can. I am a instructor and I am a student. Students are also teachers. When I get information technology right, I reach beyond the gap and tell them about Celia Cruz, Institutional Critique, and Jürgen Habermas. They tell me about Bad Bunny, Settler Mentality, and TikToks. Sometimes we have to resort to hand gestures.

five. What changes would y'all like to see in art educational activity?

I would honey it if it could be free in both senses of the give-and-take: libertad y gratis.

6. What is your educational groundwork? Did yous arrive at art from another field?

I went to a university for undergraduate studies and an art school for my master'southward degree. This has shaped me in a detail way. I learned nearly 95 per centum of what I need for my art practise, likewise equally what I demand to simply be in the globe, at the university. Allegedly, I was pursuing a caste in figurer science, only ended up with an art caste instead. My MFA gave me the other 5 pct. Although it is tempting to be dismissive of art school, the relatively small amount of things I learned there were crucial and indispensable, as they represented a very precise agreement of art as a tradition. While I believe that I might need a disquisitional, analytical, and creative gear up of mental tools to make art, I also take to understand that I am inside a tradition, and tradition requires acceptance (but not necessarily acquiescence). Ideally, there should have been a component of my didactics that included spiritual and emotional education—2 things I sorely lack fifty-fifty today.

7. How have recent cultural movements and activism informed your curriculum?

My curriculum is ever adapting to how I face the present cultural moment, and to the students who are always changing—and fast. There are times, like at present, when political awareness is loftier and I could teach a semester-long class on the arts and political movements, simply there have been times in the past, and in that location will exist times in the future, where that interest vanishes. The latter is more than challenging.

8. How much structure or independence do students take in your courses?

Both in my participatory artworks and in my seminars, I believe in very structured situations that are by and large devoid of content. This void creates a zone of liberty that the participant gets to fill up independently. For courses organized around a specific medium, I evangelize very tangible and precise technical and formal know-how, and I insist that everyone must acquire these—merely that their use for creating artworks for class is completely optional.

9. How does the program connect students to the surrounding fine art scene? How practice they larn outside the classroom?

These are two separate questions. Previously, I was at Hunter College for fourteen years, and the program really didn't take to do anything to connect students as it was already in the art scenes.

As for the 2nd question, I repeatedly co-taught a grade with Claire Bishop that never met at school. Each week, we would meet at a unlike kind of public space, come across a specialist or artist that worked in that kind of space, and discuss readings relevant to the site. 1 calendar week, we might meet in a public park and go two guided tours, one led past an urban forager and the 2d by someone studying the history of cruising in the park. Another week, we might meet in a courthouse and speak to a judge or a district attorney, and to an artist working on alternative sentencing for youth. I accept only been at Cornell for four months, simply I am already thinking of how to use the City of Ithaca as an extension of the classroom.

10. What advice do you give to your students every bit they go out school and enter the field?

ane. Yous build a career 1 viewer at a time.

two. You don't make art lonely. Form a grouping, stick together, be your own public, critic, and supporter.

3. Exist decent and kind to anybody. The intern helping you install might ane day be the curator who gives you a bear witness twenty-five years later.

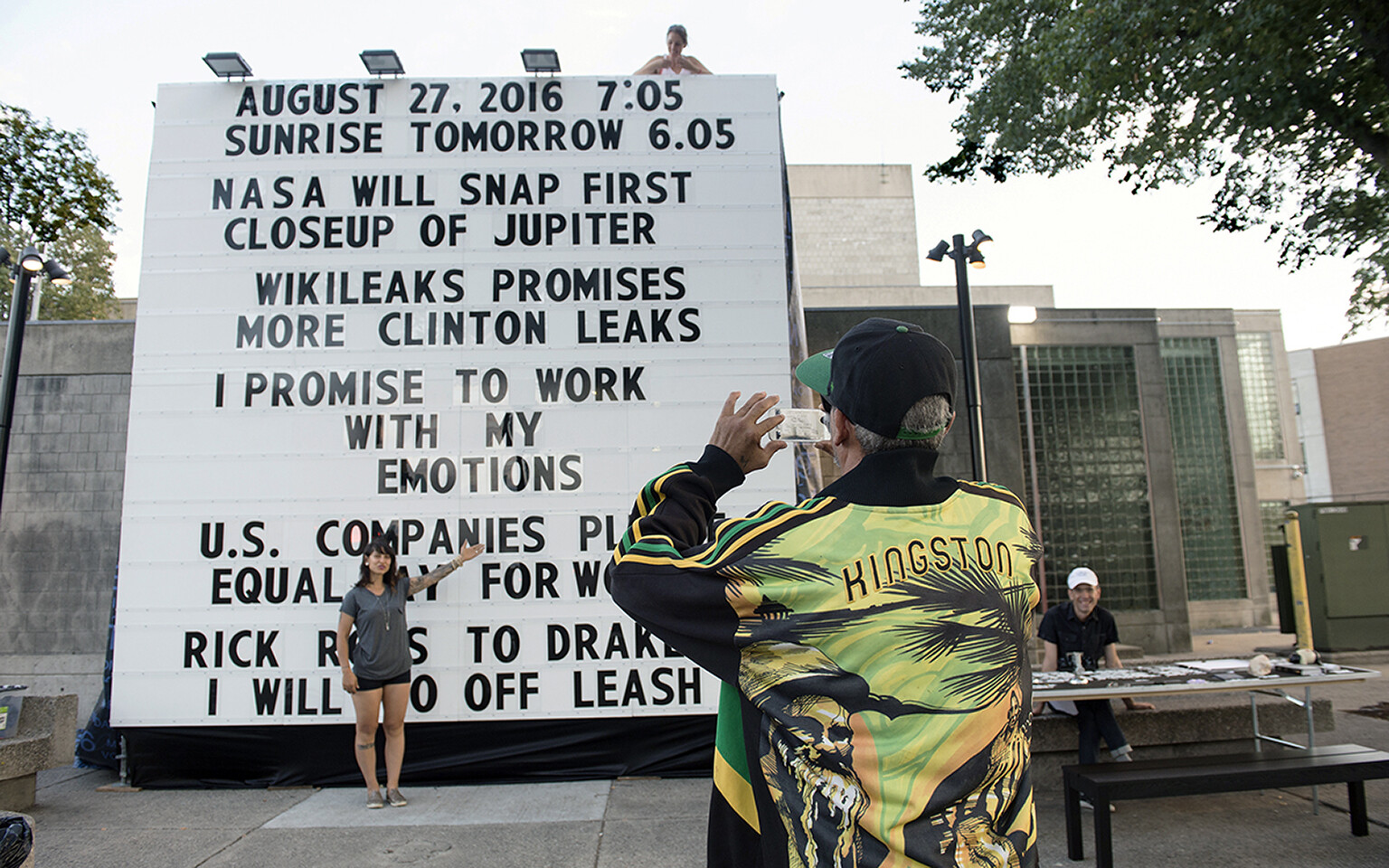

Paul Ramírez Jonas is a Brooklyn-based practicing artist and educator whose work has been exhibited extensively both nationally and internationally. Selected solo exhibitions include Museo Jumex, Mexico City; The New Museum, New York; Pinacoteca do Estado, São Paulo, Brazil; The Aldrich Gimmicky Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut; The Blanton Museum, Austin; a survey at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, and Cornerhouse, Manchester, in 2004, and a twenty-five-yr survey at the Contemporary Fine art Museum Houston in 2017. Selected group exhibitions at P.Southward.ane, Queens, New York; the Brooklyn Museum; The Whitechapel Gallery, London; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; and Kunsthaus Zürich. He participated in the 1st Johannesburg Biennale; 1st Seoul Biennial; 6th Shanghai Biennial; 28th Sao Paulo Biennial; 53rd Venice Biennial and 7th and tenth Bienal do Mercosul. His projects Key to the City (2010) and Public Trust (2016) were presented by Artistic Time in cooperation with the City of New York, and by At present & At that place in Boston, respectively.

Before his recent chair appointment at Cornell, Ramírez Jonas was an Acquaintance Professor of Art at Hunter Higher in Brooklyn, New York, where he taught for nearly xv years. Ramírez Jonas earned a BA from Brown Academy in 1987 and an MFA. from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1989. He is represented by the Galeria Nara Roesler in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and New York.

At Cornell University College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP), the study of art is an education in creating artistic objects, spaces, and experiences that reverberate intellectual judgment, philosophical agreement, historical noesis, and upstanding principles that appoint and influence the often bewildering complication of contemporary life within and across the academy.

MFA and BFA students develop the skills specific to the practice of art in addition to and inside the understanding that in that location are more than general skills necessary to a disquisitional apprehension of the collective status. This distinction is made in social club to clarify that the department does non view art itself merely every bit a profession, only as a way of agreement and communicating meaning through materials, situations, language, and images.

Source: https://www.artandeducation.net/schoolwatch/440725/office-hours-paul-ramrez-jonas-cornell-university-college-of-architecture-art-and-planning-aap